Q&A : Neutral Density Filters

/Did something happen to create a rush on ND filters? As I was preparing this post, I got a couple of other questions on the same topic. So for the three folks who wrote in, I am going to summarize your questions and try to answer them in a single post.

- Why would I need to add a filter to my lens, can't I do this when editing my pictures?

- Why would I want a filter to make my pictures blurry? I thought it was going to make the shutter open longer, but the sales guy said it would make the water blurry.

- I have seen lots of fall pictures with leaves and rivers and rocks and the water looks really smooth and like it's moving but everything else is sharp. How do I do this?

Well I'd be happy to believe that folks could get good advice in any photo retailer, but I know better. Let's start with what a Neutral Density (ND) filter is.

A neutral density filter, and I will refer to them as ND filters henceforth, is a filter that reduces the amount of light passing through the lens to the sensor. Neutral means that there is no colour shift or colour filtration being applied. ND filters come as either full, meaning the same level of light reduction is applied across the entire filter or as graduated filters that have a range from no filtration to the full effect over some span. I won't spend time on graduates here, the conversation will stick to full coverage NDs.

A neutral density filter, and I will refer to them as ND filters henceforth, is a filter that reduces the amount of light passing through the lens to the sensor. Neutral means that there is no colour shift or colour filtration being applied. ND filters come as either full, meaning the same level of light reduction is applied across the entire filter or as graduated filters that have a range from no filtration to the full effect over some span. I won't spend time on graduates here, the conversation will stick to full coverage NDs.

Some vendors calibrate their ND filters in stops, for example, 1 stop or 3 stop filters. Others refer to them as nn x where the nn is a number. This is perhaps photographically correct but is user unfriendly. So here's the simple math. For every 0.3x of filtration that's one stop. So a 0.6x ND filter cuts the light by two stops. Now you can be immune to bafflegab.

ND filters are created a couple of ways. In a popular method, the glass that the filter is cut from has a dye injected while molten. In another case, a foil overlay is applied to the filter glass. In the case of Tiffen filters, a Wratten optical gel is sandwiched between two pieces of optical glass to form a laminate. Because the colour controls in Wratten filters are long proven, and because Tiffen uses proper optical glass, they can be a very cost effective route for ND filters. Avoid the foil overlay type. You'll know because they will be very cheap. Spray painting a UV filter with grey transparent paint gives about the same effect and the same lack of quality. If you go for the dyed glass model, have your check book ready because then you want top line glass to ensure consistency of the dye base. This means either Schott or Schneider glass such as the filters from Heliopan or B+W. For your own sake, stick with one of the three named vendors.

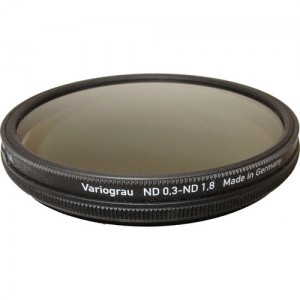

There is a special class of ND filters called Variable Neutral Density filters. Variables are not made the same way. They are two polarizing type filters, one mounted in a fixed ring and one in a rotating ring. As you rotate the front filter, the twin polarizing filters act to cut or pass light. Variables are incredibly handy because they typically cut light across a range of up to 6 stops, often from two stops to eight stops. Variables are very demanding optical units. The Heliopan units are the best out there, although I have used the Tiffen ones extensively and can recommend the Singh-Ray units as well. B+W also do variables but they are harder to find it seems.

More troubling are the stunning array of craptastic variables that cost less than the price of a single decent polarizer. These filters have no coatings and because the polarizing film being used is of such poor quality, they produce horrible amounts of moire (an optical interference pattern, click here for a full definition) and also apply a colour cast, usually akin to rotted meat green. Don't waste your hard earned money on this junk.

So to the questions...

You cannot slow down the shutter speed to create motion effects after the shot is made, claims by post-processing software vendors notwithstanding. In fact other than a UV and a Polarizer, an ND set or ND Variable is the only filter you need in your kit. Be aware that if you use a strong ND filter, your autofocus system will throw its virtual hands in the air, so you are in manual focus mode pretty quickly. Some people like variables because they can use AF with a low setting, lock the focus and then dial up the light cut.

ND filters do not make pictures blurry. That's the job of the photographer. However, strong NDs may cut the light so much that to use one without a tripod will result in blur. Typically we use ND filters to allow for slower shutter speeds in bright light so we can capture the sense of motion, such as in a waterfall or fast moving river. BTW, if you normally live in AUTO-ISO mode, this is when you want to stop that. To get slower shutter speeds you want lower ISOs, so pick a low ISO and then determine how much ND cut you want. You can also use ND filters to allow for shallow depth of field in bright light. For example, at ISO 100 in bright sun, your shutter speed would be 1/125 at f/16. If you wanted to shoot at f/1.4 you would need to move your shutter speed to 1/16000 of a second. Oops, not going to happen. Add a three stop ND and now your shutter speed only has to move to 1/2000.

If you are shooting video, which typically uses a higher base ISO, ND filters can help you significantly to get good exposures on really bright days or to allow for wider apertures where you want to control depth of focus. All professional and some consumer grade video cameras incorporate ND filters. Digital ND is the cheap solution, the higher end kit moves a physical filter in front of the sensor for better image quality.

To get that beautiful creamy water, you need long shutter speeds, and you won't get 30s exposures in daylight. Adding a 6 stop ND to a less that stops down to f/32 in our above example would get you to a two second exposure even in bright sun, and if the water is moving quickly enough you will have nice motion effect. If the day is overcast, you could get to 15 seconds. Nice and creamy.

If you want to really stop the light for really long shutter speeds in bright light, there is an answer from the Lee Filter company. Lee is best known for superlative gel filters, but they do a line of rigid ND filters that are excellent. The Big Stopper cuts a full 10 stops of light. It slides into a lens mounted filter holder because a) your camera cannot focus when it's in place and b) you can't see anything through the viewfinder when it's in place. It's whole job is long shutter speeds. It's not an inexpensive option but it works brilliantly and is available to fit most all lenses, including those with big curved front elements like Nikon's brilliant 14-24/2.8.

If you take your photography seriously, at some point you will realize that you need an ND filter. Or two. Or a variable. Also remember that in the absence of directional light, your polarizer is also an effective 2 stop ND, so you are probably already on your way.

Finally some sales people advocate stacking ND filters to cut more light. Don't. This is last resort, really. If you find yourself wanting ND filters, you want them to cut light so go big, 3 stops at the minimum.

Until next time, thanks for reading.